The sleepy village of Kilmacthomas, County Waterford, Ireland has a dark history. Fran and Conal stopped there one cold dark morning.

By Conal Healy

The words “as terrible a day as this I have never marched in all my life” have been engraved on a simple plaque on the bridge over the Mahon river in Kilmacthomas, County Waterford.

The sentence is attributed to Oliver Cromwell, when he and his army were in trouble due to the Irish weather. The year was 1649.

Laying siege to Waterford city, they had been battered by incessant rain for weeks and decided to move camp to Dungarvan. But the Mahon was in flood and held up the mighty army for a day or more.

The Mahon was the river that stopped Oliver Cromwell. (Cromwell – in some quarters – is blamed for reducing the population of Ireland by 85 per cent during his campaign there.)

Demoralised and exhausted as the Cromwellian army was, it might well have been defeated if its enemies had attacked at that point, and according to one source the course of Irish and European history could have been changed.

Cromwell was said to have described the land on his march from Waterford to Kilmacthomas in the winter of 1649 as being “a craggy and desolate place”.

Obviously he had never been to the West Coast of Ireland.

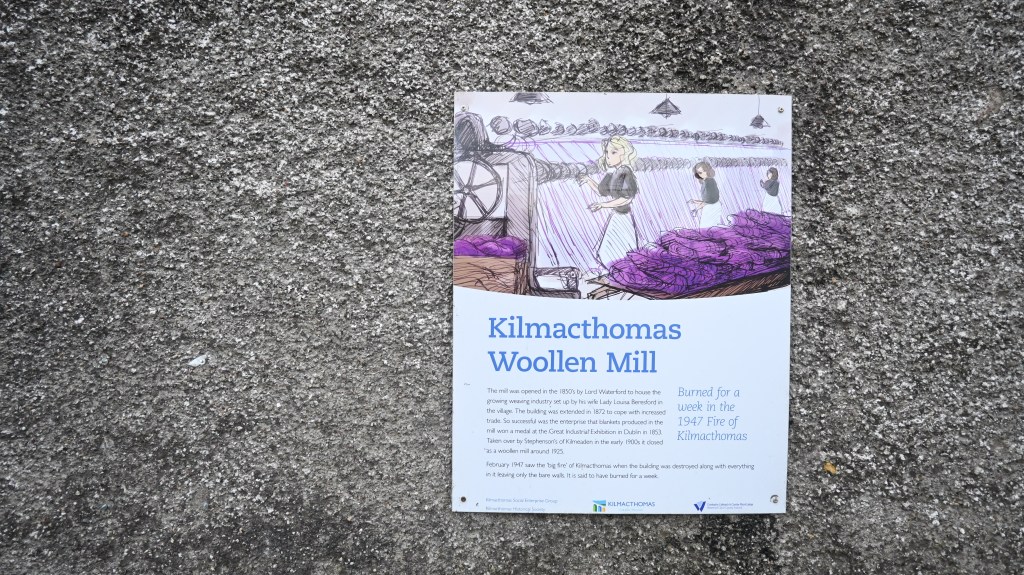

Kilmacthomas has a fascinating history, dating back to the prehistoric era. The town is home to several ancient sites. The town was also an important center for the wool industry in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Kilmacthomas Workhouse is a reminder of the village’s difficult past during The Great Famine (1845-1852). (Describing the events of Black 47 as “difficult past” is something of an understatement.)

The potato crop, upon which a third of Ireland’s population was dependent for food, was infected by a disease destroying the crop.

When a potato blight made its appearance in Ireland in the second half of 1845, it caused a partial failure of the potato crop on which so many Irish people were dependent.

When the blight returned in 1846 with much more severe effects on the potato crop, this created an unparalleled food crisis that lasted four years and drove Ireland into a nightmare of hunger and disease.

It decimated Ireland’s population, which stood at about 8.5 million on the eve of the Famine.

It is estimated that the Famine caused about 1 million deaths between 1845 and 1851 either from starvation or hunger-related disease. A further 1 million Irish people emigrated.

This meant that Ireland lost a quarter of its population during those terrible years. The Famine’s impact was most severe in the west of Ireland where some counties lost more than 50 per cent of their population.

For some people the workhouse was the only means of survival.

Abour 250,000 people suffered death in the workhouses between 1846 and 1851, and 200,000 of these are believed to have been directly related to famine-induced conditions.

Mortality rates in the workhouses were exceptionally high during these years, and they came to be perceived as ‘death houses’.

The workhouse was introduced into Ireland as part of the English Poor Law system in 1838. The British government believed it to be the most cost effective way of tackling the desperate state of poverty in Ireland. Some English politicians also believed that it would prevent the Irish destitute from swamping England.

By 1845, 163 Irish workhouses had been constructed, one per district or Poor Law Union. The cost of poor relief was met by the payment of rates (a tax) by owners and occupiers of land and property in that district.

Conditions of entry into the workhouse were very strict and entry was seen as the last resort of a destitute person. Once inside the inmates were forced to work, food was poor, and accommodation was often cold, damp and cramped.

It was in the interests of those who funded the workhouse in Ireland during the famine (through taxation), to keep the numbers of inmates as low as possible.

The Famine caused a crisis in the Irish Workhouse System.

By the end of 1846 many of the workhouses were full and refusing to admit new applicants. There was widespread shortages of bedding and clothing. Unwashed clothes of inmates who had died from fever or disease were given to the next new inmate arriving at the workhouse. There was often a shortage of coffins and burial grounds were often located close to the workhouse, sometimes next to the water supply.

As panic gripped the country, and with no other options available, there was a great rush to enter the workhouse. The road to the workhouse became known as ‘cosan na marbh’ or ‘pathway of the dead’, and over a quarter of those admitted died inside the workhouse.

The 1847 Soup Kitchens Act gave some relief to the workhouses. However, in the summer of the same year, the newly elected British Government declared the Famine to be over and ceased providing financial relief. The Poor Law Unions were made responsible for future relief measures. There were unable to cope and large numbers of people continued to die.

If you stop at Kilmacthomas (on the Waterford Greenway) it is possible to see the workhouse. There are a few outbuildings that date back to 1850.

One building has a room where hundreds, probably thousands, of corpses were stacked awaiting burial.

This room is not for the faint-hearted – there is a certain atmosphere of sadness, desperation, grief that seems to ebb out of the walls.

The Kilmacthomas Workhouse was closed in 1919 and the site is now being developed for residential purposes.

Leave a comment