Fran and Conal reach the middle of Ireland – in time for lunch. It’s a Stephen King meets Hotel California vibe as they enjoy a meal in Athlone.

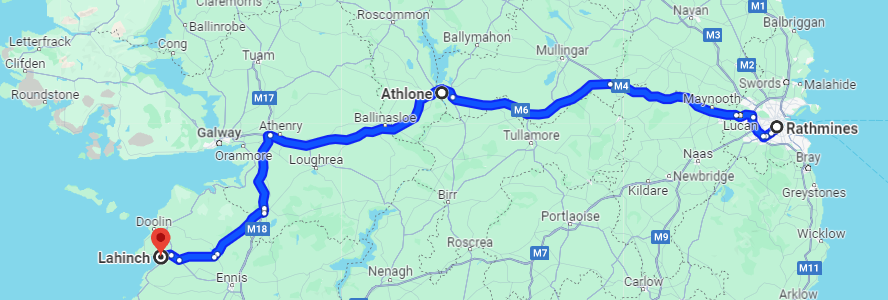

Wednesday, October 11, 2023 (Lunch): It was just after 1.30pm when Fran and I stopped for lunch at Athlone. Athlone is in the centre of Ireland, located on the banks of the mighty Shannon River. The town dates back to the Bronze Age and has been strategically important for over 1000 years.

Athlone sits on the border of County Roscommon and County Westmeath, Ireland, in the province of Leinster. The town is situated near the southern shore of Lough Ree, with the River Shannon splitting the town in two.

A garrison town, Athlone was recognised down through the centuries as an important crossing point on the River Shannon.

DRAWN TO THE CENTRE

I have been coming to Athlone for about 50 years. My late father would take the family to Achill Island every August for the annual summer holiday. In those days (in the 1960s) the trip of 300kms would take six hours. This included stops to see various relations (for tea and cake).

Another designated stop on the trip west was for at a bakery in the main street of Athlone. It was a chance of us (four kids and two adults) to stretch our legs, and probably for my parents to stock up with cakes before visiting the extended family.

I had been to Athlone as a passenger in a car, on a coach, and a train. Now in 2023, I driving into the town. A first for me.

Athlone on a grey, cold late autumn afternoon was … I have to say, a depressing dump.

The main street had been ripped up (there is a beautification scheme in place) so there were plenty of roadworks, diversions and the town looked a mess. In a few years it should look great, but not on this particular day.

Fran and I stopped to stretch our legs. We admired the St Mary’s Church of Ireland (we would have gone it, but it was shut). We find a coffee shop that sells only coffee and cake (to use the toilet, I’ll admit), then went across to a department store called Dunne Stores and I buy an Irish winter fake puffer jacket. It was that cold.

TIME FOR FOOD

With our stomachs rumbling (it was 1.30pm), we decided on lunch at the Café Bonne Bouche.

Stepping inside the café was like being transported back 50 years. The manager (and probably the owner too) welcomed us and showed us to our seats. Each table had a hand-drawn number on it.

He listed the lunchtime special (“Chicken with stuffing”, we were told).

And handed us the menus and left us to check with the other diners. He returned a few minutes later to our table and diligently took our order – Soup of the Day with Brown Bread and a Pot of Tea – on his small notebook.

This was something from another era. It had a feeling of Hotel California about it. The handful of people in the café (I want to called it a tea house) ate in silence.

You could almost imagine a wall clock ticking. We noticed the sachets of sugar had Irish sayings on them (in Gaelic too) – “To the black crow its offspring is bright”. Is this a Stephen King kind of warning? I wondered?

You could almost be aware of time passing, maybe even slowing down. After lunch would we step outside and discover 30 years had passed?

The soup was great, the brown bread fresh and the pot of tea … restorative.

On the way out, Fran bought a slice of the café’s whiskey cake. Wrapped in cling film, the cake was bought as an emergency … in case something went wrong, and we ran out of food.

Despite our fears, we stepped out in Athlone in 2023 – the café was no Hotel California.

CROSSING OVER

Determined to walk off the soup, Fran and I set off to explore Athlone. We crossed the bridge across the Shannon and went from Leinster to Connacht. Wandered up to the 13th Century Athlone Castle, just in time to see it invaded by a bus load of tourists. We backed away.

A walk by the river took us past a group of what appeared to be crystal-meth addicts who were arguing with each other.

We passed an IRA Memorial is a memorial in Athlone, County Westmeath. The memorial is dedicated to the Athlone Brigade of the Irish Republican Army that participated in the Irish War of Independence and Irish Civil War. It is the only statue I have ever seen where the subject is holding a revolver.

We saw a couple feeding ducks and seagulls in the river. Walked through a park where a sign warned “No Shooting”.

We wandered back to the car, happy to be leaving Athlone despite the hire car starting to smell of the bags of rubbish.

We re-crossed the Shannon and entered Connaught. We were stepping into a place with a lot of history.

INTO THE WEST

My father, John, grew up in a small town in the west of Ireland, in County Mayo. It was a town that was slowly dying, largely due to waves of immigration. There was nothing to keep people there. There were jobs elsewhere – Dublin, London, Boston, Sydney. So, people left, usually never to return.

My father was one of them – he left Mayo for Dublin to pursue a career in journalism.

Mayo wasn’t the only county to suffer – there were other: Sligo, Galway, Clare, Roscommon, Leitrim.

It seemed they had one thing in common, they were all located west of the Shannon River.

In 1969 my father published The Death of an Irish Town (now titled No One Shouted Stop) which chronicled the economic and social decline of rural life in the west of Ireland in a time of widespread poverty and mass emigration.

To my father is seemed that successive Irish Governments had turned their backs on The West. To them it was a lost cause. It seemed that politicians believed there was no need to invest in a place that was slowly becoming a wasteland.

My father championed The West, campaigned for resources be diverted from the prosperous East Coast to the area beyond the Shannon. The turning point came when Ireland joined the European Union (in 1972) and funds started to flow to the West.

In European terms, the west of Ireland was one of the poorest places in Europe. The EU didn’t want people from the poorer parts of Europe (Southern Italy, parts of Greece and parts of Spain) gravitate from the edges to the centre, ie the richer areas. It made better sense to invest in the edges.

In real terms, this meant that new roads were built in the west of Ireland, phone networks (that still relied on switchboard operators in 1982) were upgraded. It meant many houses now got indoor plumbing.

(The Wild Atlantic Way is another inspired Euro-funded project.)

Since then, more than 42 billion Euros (about Australian $69,344,929,200) from Europe Community has landed in Ireland. Irish farmers receive 1.2 billion Euros (about Australian $1,981,446,000) every year from European coffers. This is in a country with a current population of five million.

It is almost ironic that places that were once regarded as wastelands (ie bog lands) are are protected habitats under European and Irish Law and representative samples have been designated either as Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) under the EU Habitats Directive or Natural Heritage Areas (NHAs) under the Wildlife Acts.

The once wastelands are now tourist attractions. In fact, in under one particular bog in north Mayo archeologists discovered a Stone Age site dating back approximately 5500 years, some 2,500 years before this type of field system developed everywhere else in Europe.

(My father, who died in 1991, would have been proud to see the changes he had campaigned passionately for come into being.)

A SPOT OF HISTORY

In Irish popular memory, the English English statesman, politician and soldier Oliver Cromwell (in the 17th Century), is said to have declared that all the Catholic Irish must go “to Hell or to Connaught”, west of the River Shannon.

The Cromwellian transplantation of sending Catholics to the West is often cited as an early modern example of ethnic cleansing. Cromwell detested the “Irish as primitive, savage, and superstitious” according to the Britanica.com.

During Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland (starting in 1649) 600,000 men, women and children were killed.

Some estimates of the drop in the Irish population resulting from the Cromwell’s campaign reach as high as 83 percent. About 50,000 people were transported as indentured labourers to the English colonies in North America and the Caribbean.

Cromwell’s soldiers (The New Model Army) who served in Ireland were entitled to an allotment of confiscated land there, in lieu of their wages. As a result, many thousands of New Model Army veterans were settled in Ireland.

The Irish Catholic land owners were told to vacant their land and move to the agriculturally poor land west of the Shannon.

They had a grim choice: “To Hell or to Connaught”.

Leave a comment